We agreed to meet at a linguistics conference in the city of Salta. Our common interests were joining the sessions on glottopolitics and sociolinguistics and scant opportunities to discuss current research on the country’s indigenous languages. We wondered whether the topic had made it on the research and academic linguistic event’s agenda, after the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the period between 2022 and 2032 as the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous Languages.1

Iván Arjona Acoria is the ckantal (ancestral authority) of the Comunidad Originaria Rural Atacama de Raíces Andinas (Atacama Rural Indigenous Community of Andean Roots) in Los Andes, Salta, and also member of the Pueblo-Nación Atacama Network. Twenty years ago, he made a commitment to research and become an expert on Kunza, the language of his people, which in English means “what is ours.” Since then, he takes advantage of all events on linguistic studies to explore various research methodologies and policies to promote indigenous languages, community engagement processes, and the profiles of researchers doing this work. Iván believes these type of settings are serve to gain knowledge and resources, although it is hard not to draw comparisons between the standpoint and strategies proposed by professional linguists— who are often outsiders to the communities of speakers they are researching—and those like Iván who practice traditional community education.

People’s drive to rescue and revitalize Kunza, the Lickanantay or Atacama people’s language, emerged initially in Chile in 1980, as a way of refuting those linguists, folklorists, and anthropologists who declared Kunza an extinct language, convinced that it was no longer spoken fluently. The communities knew, however, that the elders kept the language almost intact in their memories, and that many of these concepts were prevalent in everyday use. Kunza words are not vestiges of a lost language but continue to organize the Lickanantay people’s reality and help safeguard their deepest culture and spirituality practices. Kunza thus becomes their ancestral cartography: it provides order to the natural environment and living creatures, it is used to describe their crafts and bartering activities, it names their divinities, and it is used for ceremonial songs and keep sacred rites alive.

At the end of 1990, the Atacama Nation-People Network, a centralized and self-sufficient indigenous organization with the task of representing the locals before the federal government, was created by the Atacama communities that live across three countries—Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina—spread through what has been historically Lickanantay territory. The network’s foundation is based on a set of ancestral practices that continue to this day, such as bringing together the tornas (socio-family groups) scattered across the Argentinean Puna and the Chilean and Bolivian desert. For example, to organize the distribution of water at the local level, the network calls for an assembly through the Talatur (springtime song and dance ceremony). Meanwhile, the Muckar (a commemoration and cosmic link with the ancestors),2 are larger gatherings that bring together local authorities and other members of the communities, regardless of the country in which they reside, to help establish the barter calendar and support llama and donkey rodeos.

Josefa Cruz Carral makes reference to the Talatur. Source: Ckunsa Ttulva.

The Atacama Nation-People Network symbolizes the Lickanantay people’s kinship and their legitimacy based on three pillars: shared territory, a common history, and a common language. These three pillars also helps the Lickanantay map their territory. From the outset, these communities sought to maintain their ancient cultural and “commercial” ties, despite border restrictions that prevented free transit from one country to another. Later, the organization broadened its scope to support and intervene in local people’s struggles. Thus, for vulnerable communities without legal federal recognition, such as those in Salta, this network not only guarantees political representation but provides a safe haven for then and a place to build collective strength.

As part of a decolonization process of reclaiming the Lickanantay identity, the Atacama Nation-People Network’s efforts to revitalize the Kunza language is key. It is also a way of honoring the memory of their ancestors, who bravely resisted the violence of colonization and its aftermath. The fruits from the network’s research has and will help these communities nurture this ancient language for generations to come. Alongside this duty, there is a desire of bringing the voice of Ckuri (Great Wind Spirit) back to nature, thus restoring balance and harmony inherent to Ckausatur Ckayahia (Buen Vivir). The revitalization of their native language means repairing an interrupted dialogue between present-day communities, their ancestors, and shelter provided by living Nature. Only by reestablishing this communication can the Lickanantay people delve into their past and recover their deepest historical roots and cosmovision.

The Ckuri Legacy

The Atacama elders tell us that their language is a gift from Ckuri, transmitted to human beings thanks to the mediating action between the herabun (culture and language educators) and the Ckonick (Lickanantay spiritual sages). The language’s origin determines its substance: the hoarse voice of the wind resonates in Kunza, along with other particular sounds from nature. Researchers such as Francisco San Román (1890) and Aníbal Echeverría y Reyes (1966) argued that its difficult-to-pronounce guttural sounds imitate their surroundings, characterized by a hostile environment. In contrast, the elders believe that nature is speaking through their language, and that Kunza’s features are specific to the story of its origins, its genealogy traced through each word: when people cut dry wood, the winds flowing through the Macón mountain range, the sirens’ songs heard in the water springs, etc.

There are those who argue that Kunza does not show similarities with any other language from the surrounding area, such as Quechua, Aymara, or other ancient languages that Atacameño communities used to speak. According to Julio Vilte Vilte, this is because Kunza belongs to the macro-Chibchan family and the Paezano subfamily, native to the Amazon region of Colombia and Ecuador. The author bases this linguistic affiliation on the early history of the people. According to legend, there was a time when two cultures, one from the Amazon and the other from the Altiplano, that had been in conflict for a long time, agreed to meet in Laratchi to try to resolve their differences. As a symbol of peace and integration, they exchanged two types of ceramics: a polished red (lar or lari) ceramic and a shiny black (atchi) ceramic. The union between these two cultures would eventually give rise to the Lickanantay people, although some believe there is third unknown branch.

The origin story of the Kunza language can be traced to the influence of three different ancestry lines, so claiming that it is uniquely positioned under the Amazonian language family tree presents some problems. There are traditional educators who, safeguarding the uniqueness of Kunza as an isolated language, have carried out comparative studies with Andean languages and determined shared “typological” characteristics. They have found that, similar to most neighboring languages, Kunza is polysynthetic,3 its words composed from the sum of morphemes. Additionally, it is a glottal language, a phonological feature inherited from Aymara, unlike Quechua. These researchers’ perspective take into account the social and historical influences on the language’s development, such as the environment where the Lickanantay communities live, free migration through ancestral territories, and the continuous contact between speakers of different languages.

The herabun who claim Kunza is an isolated language, beyond the fact that it has common elements with the nearby Andean languages, draw a temporal parallel with Puquina.4 Kunza is over 10,000 years old, which means that it must have been contemporary with the original languages, traces of which are still preserved today. Unlike Puquina, Kunza did not have the same influence and splendor because the communities that spoke it were much smaller and the areas where they settled—the extensive salt flats of the Puna desert, 4500 meters above sea level—influenced on their seclusion. Paradoxically, these conditions also allowed the language to survive over time.

Language is intertwined with the origins of societies, therefore, rescuing a language leads to unraveling the obscure knots of history. Thus, when listening to the aspirated and glottal words of Kunza, which generate sudden plosives, we are able to disturb the silence and the worldview of one of the oldest surviving cultures in Latin America.

Historical Twists and Turns

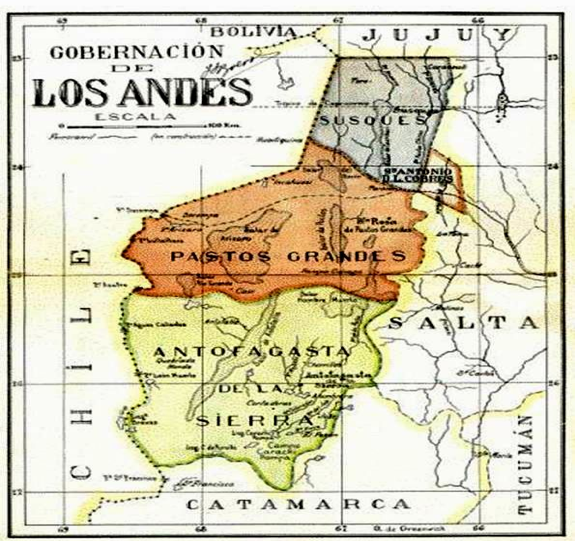

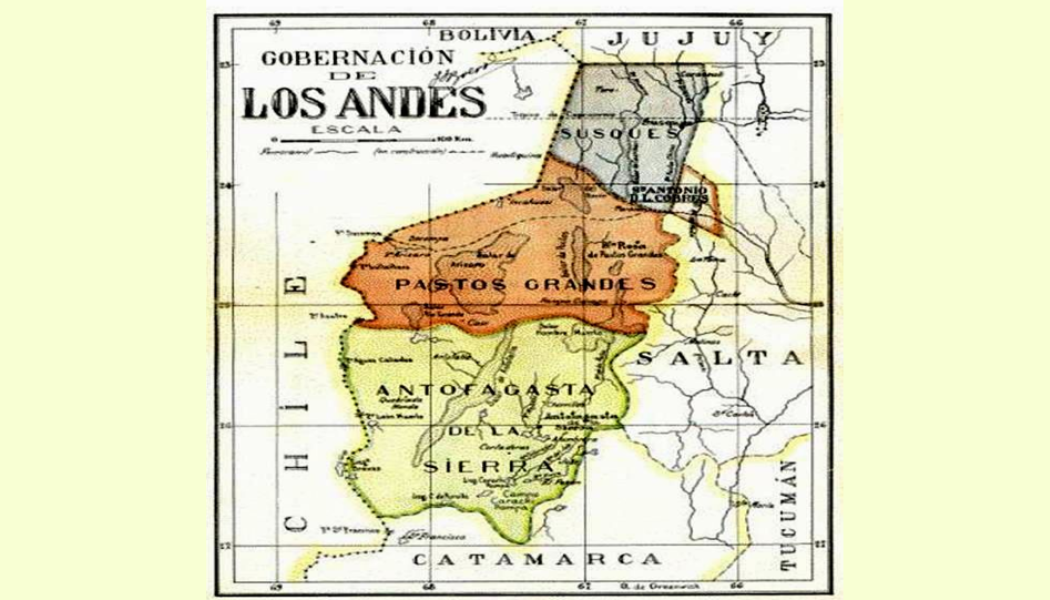

When the territorial boundaries of what is today known as Argentina were finally defined, the political project was to establish the Andes region, based on geographical and cultural justifications, as just another province. Thus, the General Map of 1910 shows a jurisdiction that extends exclusively through the Puna region—today’s Jujuy, Salta, and Catamarca provinces, and their main towns: Susques, Pastos Grandes, and Antofagasta de La Sierra. Although the project failed,5 it highlighted three significant issues: the geophysical particularity of the area and the arbitrariness of national borders, an attempt to politically annex a region that bears more similarities to the Chilean desert on the other side of the cordillera and the Puna in southern Bolivia. Finally, it outlined the territory that the Lickanantay Nation had occupied since times immemorial.

As we mentioned in the previous section, the rustic quality of the Kunza language and other archaeological data reveal that the Atacameño culture is thousands of years old. Its endurance and resistance to the violent onslaughts of history are due, to a large extent, to the environment in which the communities live and their ways of social organization. People settled on these ancestral high-altitude plains, which are characterized by a dry climate and extreme temperatures, ranging from freezing to scorching heat. The tornas, generally made up of a few families, tend to settle near a meadow or spring that provides them with drinking water and irrigation for their crops. These water sources are few and far between, which is why tornas live so far apart, however, they always find time to meet up at festivals, spiritual ceremonies, bartering assemblies, among other occasions. Caravans traveling through the territory offer their goods and act as messengers between the scattered groups.

During the expansion of the Inca empire, which began in the last decades of the 15th century in what is today Argentina, the Lickanantay people retained their freedom and right to continue their cultural practices, including the use of their language. The Inca empire integrated these communities politically and maintained commercial ties with them. In order to sustain these relationships, the Atacama people learned both Puquina, which was spoken by the nobility, as well as Quechua and Aymara. The coalition between the two groups was such that, by the time the Spanish landed in their territory, the Lickanantay society was in the process of becoming a feudal system. They had started to build pucarás (strategic militarized enclaves), such as Lasana, Turi, and Quitor (today’s Chile) to deal with conflicts with the other subjugated peoples who, by then, had made several attempts to revolt.

The Spanish domination led to a weakened Kunza language, forcibly silencing it and confining it to the private family sphere. The colonizers’ initial plan was to subdue and evangelize through the use of Spanish, but this failed due to the impossibility of communicating with the indigenous people on occupied land. They then resorted to Quechua and Aymara as lingua franca, beginning a process of strategic alliances. This linguistic policy lasted until the end of the period of the conquest, when Carlos III declared Spanish the only official language in the colonies, through coercive measures. In the Atacama region, financial and physical punishments were established, to the point that those who dared speak Kunza had their tongues cut out. Transgression was penalized with violence, while those who adopted Christianity and Spanish were favored with access to economic activities and high positions within indigenous society.

Later, the policies adopted by the newly-formed Argentine state further stifled the Kunza language, which after a long period of silence had begun to resonate once more in the Atacama highlands. In a quest to build a free and sovereign republic, priority was given to the promotion of a homogenous cultural identity with a point of reference in Europe, despite its call for autonomy from the old continent. This meant delegating schools the task of making this project a reality. According to Teresa Artieda,6 this period followed a postcolonial educational framework with one cultural system and one writing model, where Spanish became the official national language, and, not coincidentally, educators were often outsiders.

In Salta, the process of integration of Puna communities into the Argentine national state did not occur the same way. The groups from the lower Puna adapted quickly to the governmental institutions and ordinances, but for the families from the “extreme Puna,” this process was more difficult and often involved violent coercion. For example, families were forced at gunpoint and in the presence of the police to send their children to Catholic primary schools which, in turn, became foster homes. This policy separated children from their communities for long periods of time (up to ten months), breaking their connection with their cultures and native languages. The schools replicated the same mechanisms of repression for speaking differently and expressing other ways of understanding reality, as evoked by a witness account recovered by Iván Arjona Acoria:

We often used words that came from Kunza or Quechua in Atacama communities, but at school, using those words was considered speaking badly. It was seen as vulgar language. I remember we used ch’umpi for the color brown. But the teacher would then hit you or pull your ear while correcting you, saying, “Don’t say ch’umpi, say BROWN!” […] This ongoing form of [repression] in the use of language led one feeling ashamed of one’s own language (2019: 139).

Back then, persecution and punishment was commonplace for practicing activities and ceremonies not recognized “within the national cultural model.” Until the end of 1980, the ceremony to honor Paata Hoyri (Mother Earth) was so discredited that it was considered a public-order crime. The police would arrive and use repression tactics against anyone gathered to pay homage to Mother Earth. Because of this, families began to hold their ceremonies clandestinely, at night, and with the necessary precautions to avoid attracting attention.

Military service was another institution created to sustain the nation-state, forcing young people to leave their communities and submit to a pedagogy of strict obedience. The experience of the colimba or conscription could reaffirm a recruit’s desire to return to the homeland, or the opposite, break their connection with the community and lead to a desire of residing in different places with other ways of life.

Equally important, infrastructure projects developed in the Puna or nearby also had an impact on weakening Kunza. For example, in 1921, the US engineer Richard Maury undertook the construction of the C14 railway branch line through the eastern mountain range, from Salta to the Port of Antofagasta in the Pacific. This project led to the migration of men and women from different Atacama and Tastil communities who joined the workforce and, consequently, used Spanish as their primary language for day-to-day communication.

Fast forward to today, the Lickanantay people fighting for their legal recognition, lacking a jurisdictional status, are still excluded from policies (even those aimed at indigenous peoples) and find themselves in an increasingly vulnerable situation. As with other original nations, their struggle was given fresh impetus by the creation of the National Institute of Indigenous Affairs (1985) and the incorporation of Article 75, Section 17 under the Argentine Constitution (1994), which not only recognizes the preexistence of diverse ethnic and cultural groups throughout the country, but also explicitly recognizes their rights with respect to their identity, their territory, and access to other social benefits essential for a life with dignity.

Memory Work for the Revival of Kunza

People who teach traditional education believe that a language that is no longer spoken fluently is not necessarily a dead language. A simple sound log or registry, basic dictionaries, or rudimentary studies documenting basic grammatical structures and part of the lexicon can bring a language back from its so-called extinction. In this sense, Kunza studies carried out since the 19th century—there are even records of these studies in colonial texts—are fundamental to its revitalization process. The herabun understand this and use existing documentation to expand on what has been collected, rectify some errors, always working from and for the community, reaching the most remote corners of the Puna, where their language has been preserved in a more unscathed state.

The ability of Kunza to adapt to the twists and turns of history has been key to its survival. Its agglutinating nature, where concepts merge with each other to form words, gave rise to combinations between its own terms and concepts from other languages in the surrounding environment. For example, rumiara is a word composed of the Quechua rumi (stone) and the Kunza hara (lodging), or stone lodging. Likewise, in the Puna of Salta, more than 600 words in the Kunza language have been identified and are used daily alongside Spanish. Their unique sounds subtly invade the dominant language, giving the Atacama people a unique way of expressing reality and filling the space with multiple meanings. Gestures and body movements, inherited from timeless origins, also contribute to the construction of meaning and dialogue, enriching the community’s linguistic behavior.

The work of safeguarding the Lickanantay linguistic heritage in Salta was initiated by Don Romualdo Fabián of Paraje Olajaka, together with other members of his community, including young Iván Arjona Acoria. Their project consisted of documenting the language’s toponyms, words and expressions, as well as collecting oral histories, preserved in the memories of the elders. The geography they identified for this documentation was very broad, because the Comunidad Originaria Rural Atacama de Raíces Andinas (Atacama Rural Native Community of Andean Roots), under the representation of Don Romualdo, included two of the oldest and most important “urban” settlements in the Argentinean Puna: the community of Sicko, on the banks of the Salar del Rincón, and the Mamaturi (mother’s residence), located on the edge of the Quevar Volcano.

Ivan recalls this experience:

In order to recover oral histories, we began by recording and writing them down. We started with the oldest people because time warranted it. During the second phase of the project, which is still in progress, we included people ranging from 40 to 60 years of age. We chose people from three different places: Macón, the Quevar volcanic circuit, and the Chapur region. These places were selected because we all descend from the same surname and, in principle, it was easier to work among relatives since contact is made more quickly and there is usually no objection (2019: 142).

Don Romualdo carried out this work in isolation until the creation of the Atacama People-Nation Network, when communities from the three countries gathered together, and they were able to share the progress of their research and the goals they wanted to achieve. This encouraged the researchers to document the phonological, morphological, lexical, and grammatical of present-use Kunza in the territory. Later, the remaining provincial communities joined in: Matancilla, Corralitos, Rangel, Casa Colorada, Esquina de Guardia, Esquina Blanca, Tipán, Cerro Negro, Cobres, Aguas Blancas and Incahuasi, scattered across the Los Andes province and the northern sector of La Poma region. The researchers also defined some common elements to guide their research:

- Although one of the goals is the standardization of the language, research should revalue variations inherent to their contexts, which, in short, means showing the vision of each reality throughout the length and breadth of the ancestral territory. For example, see the Unified Dictionary of the Ckunsa Language published in 2021, edited by the Lickanantay Linguistic Council of Chile.

- The category of herabun was agreed upon to refer to those who put traditional education into practice to safeguard the local culture and the Kunza language within the educational and community spheres. This task brings together the scientific rigor of language studies and the depth of the ancestral human spirit.

- Work from and for the communities is encouraged, which implies rethinking and implementing methodological strategies that respond to the needs of each context and social group. All work must be validated by the communities.

From the point of view of traditional educators, the documentation of Kunza in the tornas provides a pedagogical purpose. Consequently, Kunza research has led to the elaboration of didactic materials, authored by the community or individuals, to allow teaching the language to new generations. In the case of the communities of the Puna of Salta, the finished booklets7 are being reviewed by the people who are part of the Atacama People-Nation Network’s traditional educational program. While the material is being edited, adults, especially mothers, have begun to cultivate the language in the communities, teaching children phrases and songs in Kunza or substituting words in everyday speech, as Iván points out:

We started inserting Kunza words into our daily speech instead of Spanish words and thus began to name things in our own language. For example, [we no longer say lagartija (lizard) but use instead chaltím], and we no longer call a mouse huk’ucha, which is a Quechua word, but now we call it ckilir. Thus, slowly, we are reclaiming our language, because both Spanish and Quechua have had a strong influence in our region (2019: 142).

| The ancestral cartography of the Comunidad de Raíces Andinas Many topographic terms incorporate the foundational legends from each place to create an ancestral cartography of the Comunidad Rural Atacama de Raíces Andinas. Exploring the semantic components of the toponyms can help to rescue the sacred history hidden in each corner of the Puna of Salta. Some examples include: |

| Pom-Pom | “Silence” or by extension “the silence of the Pampa,” to describe the desertic Pampa near Caurchari, historically used as a post for cattle ranchers, particularly during the winter season when snow is used as a resource to obtain vital water. |

| Chapur/or | From the Kunza tchapur, which means “ Fox Hill” or “ Fox’s watering hole”. It is a very tall mountain located on Route 37, surrounded by a large salt flat and small meadows. It is a place often frequented by and refuge for the Atacama muleteers on their way to the Calchaquíes Valley, in search for corn and potatoes. Nowadays is known as “Centenario”, a name imposed by mining capitals for the exploitation of minerals. |

| Chuchu | “Boob or woman’s breast”. It is a hill located by the meadows of Aguas Blancas, its summit is brownish black due to the presence of slabs and black stones. Also called Cerro Chulo through a corruption of the original Kunza word. |

| Quirón | From “quiri or quiro”, which means “beautiful place.” It is a landscape formed by a wild ravine of medium depth and low multicolored hills separated by a large plain. It is located on Route 37, near the town of Salar de Pocitos. |

| Patta, Abra de | “Mother”, which means “ Mother’s Pass.” It is located on the highest point of the Route 27, near the Macón mountain range. There is a beautiful Atacameño oral traditional legend that refers to this name. |

| Tocomar | “Worm.” It is a place located on the side of Route 51 at the foot of the Abra de Chorrillos, comprising a large plain with areas where hot springs flow. |

| Nezur | “Pattern of peach colors, not cheerful.” The name given to a place in the Quiron region, where the colors of the earth are vividly layered. |

| Yudi | “Split roads.” It is a place with small hills adjacent to Caurchari, where there used to be a road to Sucarcasto and Catua. |

| Sutarckato or Sucarcasto | From the combination of “sutar” (hummingbird) and “ckatu” (egg). It is translated as “ hummingbird’s egg,” or its literal derivation, “place where the hummingbird nests.” It is a place located on Route 27, consisting of a large, wide, deep ravine where there are a lot of springs with meadows that reach the foot of the Quevar Volcano, on a westerly direction. |

The herabun’ s challenge ahead is making sure that the materials produced in the communities are used by the educational institutions located in the ancestral territory. Additionally, being able to participate in the teaching process in the local classrooms. Unfortunately, achieving this objective is not possible as long as the provincial government does not recognize the preexistence of the Atacama people in its jurisdiction. As a result, their rights to a bilingual intercultural education, sovereignty over their territories, and other vital rights have been postponed indefinitely.

In spite of how immeasurable the work seems at times, the results are gratifying: Alabalti, Alabalti (welcome) the good harvests! Last year the University Language Center at the University of Buenos Aires presented an interactive Map of the Indigenous Languages, where Kunza appears alongside twelve other identified languages in Salta and other native languages undergoing a process of revitalization, such as Lule and Kakán. This national recognition contributes greatly to the struggle of the Atacama people for their identity and culture rights.

Likewise, by consensus of the Atacama People-Nation Network, the communities of Salta are in charge of managing and organizing the Second Congress of the Kunza language, which is a significant gesture of confidence placed on the traditional educators’ trajectory. The Salta delegation participated in previous events organized by the network to encourage the exchange of experiences and goals of reclaiming their language. Panels included the “Seminar on the Lickanantay’s history and language” (2004), the “Workshop to raise awareness for the rescue of the Kunza language” (2016) and “Semmu halayna ckapur lassi ckunsa” (the first large meeting held in the original language), in Calama in October 2021. Attendance during these activities strengthened the link between the herabun from the three countries and specialists in language studies committed to their cause.

The work is hard, expectations are high, and the desire to restore Kunza to nature is becoming a reality. After several centuries of violence in all its forms (physical, epistemic, and linguistic), the voice of Ckuri is beginning to be heard beyond the adobe, stone, and mud homes that border the Puna of Atacama. Mothers and fathers generously teach their people’s history, using their ancestors’ words and phrases, because in the Ckoi kunza (our voice) all generations sound in unison. These are neither whining nor abrupt cries, the voice of Ckuri interrupts the silence with the serenity of those who know with certainty that their journey might be slow but clear and unstoppable.

- The objective of this proclamation is for nation-states and relevant organizations to become aware of the plight of many native languages and to mobilize and provide resources for their preservation, revitalization, and promotion. ↩︎

- The Muckar is celebrated from October 25 to November 2. ↩︎

- Most Amazonian languages are also agglutinative. ↩︎

- Much later, the Incan Empire assimilated Aymara as a language and, finally, acquired Quechua for the administration of Tawantinsuyu as part of their legal-economic strategy. ↩︎

- For more on the project see: “‘Los Andes’, la provincia argentina que no fue, pero que tuvo 22 gobernadores”, MDZ, May 22, 2019, https://www.mdzol.com/sociedad/2019/5/22/los-andes-la-provincia-argentina-que-no-fue-pero-que-tuvo-22-gobernadores-29213.html. ↩︎

- Teresa Artieda, “La interculturalidad en educación ¿un enfoque necesario o una moda pasajera?,” presented at the IV Congress on Provincial Education: Mirar las huellas, dar nuevos pasos, September 26-27, 2024, https://youtu.be/J3KxWFpxmjQ. ↩︎

- The communities are at different stages in their research and material output. There are some that are still documenting their language. ↩︎

Bibliography

Arjona Acoria, Iván. (2017) “Referencias Históricas de Nuestra Lengua Kunza. Historia de la Comunidad Originaria Rural Atacama de Raíces Andinas”. Mimeografiado. pp. 23-28.

Arjona Acoria, Iván. (2019). “El patrimonio atacameño en el presente”. Patrimonio y pueblos originarios. Patrimonio de los pueblos originarios. Félix A. Acuto y Carlos Flores (comps.). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Imago Mundi.

AA.VV. (2016). Grafemario unificado Consejo Lingüístico CKunsa Lickanantay.

Manual de trabajo para cultores y educadores tradicionales. San Pedro de Atacama.

Brizuela, Analía. (2021). “El ramal C14: de la fiebre del salitre a los sueños del litio”. Página 12, 22 de agosto. https://www.pagina12.com.ar/363124-el-ramal-c-14-de-la-fiebre-del-salitre-a-los-suenos-del-liti.

Comunidad Likan Antay Corralito, Salta. (2019). “El transitar del Pueblo Atacama”. Patrimonio y pueblos originarios. Patrimonio de los pueblos originarios. Félix A. Acuto y Carlos Flores (comps.). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Imago Mundi.

Consejo Lingüístico CKunsa Lickanantay. (2021). Diccionario unificado de la lengua ckunsa. Manual de trabajo para cultores y educadores tradicionales. Santiago de Chile: CONADI.

Torrico-Ávila, Elizabeth. (2021). “Insurgencia detrás de la enseñanza de la lengua de los atacameños”. Temas Sociales, 49-noviembre, pp. 216-236. https://doi.org/10.53287/afrs4691ow80u.

Vilte Vilte, Julio. (s/f). Kunza. Lengua del pueblo Lickan Antai o Atacameño. Diccionario Kunza-Español, Español-Kunza. Chile: Codelco. https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/archivos2/pdfs/mc0038216.pdf.

Vilca, Tomás de Aquiro. (2022). “Despertar de nuestra lengua ckunsa: Lassi ckunsa nisaya ckepnitur”. Presentación. https://peib.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Reviviendo-la-lengua-ckunsa.pdf.

-150x150.jpg)