On August 31, 2021, the Municipal Council of Potosí declared the women’s collective “Mujer de Plata” as “personas non gratas” for coauthoring more than a dozen graffiti on Potosí’s heritage sites. However, the members of the collective took this decision as an impetus for their fight against injustice towards women. Instead of feeling silenced, they embraced and celebrated being “personas non gratas” but “against machismo,” taking it as a slogan for their rebellion.

Angela Uzuna Bobarin, co-founder of Mujer de Plata, painting graffiti in the old town of Potosí, Bolivia.

Beginnings

“Most of the collectives are Catholic,“ which is why we ‘created a space for informal and relaxed reflection, with no intention of doing something so powerful,” said Evelyn Callapino, co-founder of Mujer de Plata. She was looking for rebellious, outspoken non-conformists among her friends in Potosí, and that was how she met the first members of the collective. She wrote to them and asked them to be friends because she didn’t have any friends in Potosí due to its conservative mindset.

Potosí is one of the most conservative regions in Bolivia, which is reflected in the local phrase “the faithful and fine Potosí woman”, alluding to the fact that Potosí women should be quiet and submissive, not argumentative. It is frowned upon to protest or shout, and it is also one of the poorest regions. “In Bolivia, Latin America and the world, [Potosí] is one of the hubs [of colonialism], and it was important for something to emerge from here.” At the same time, Evelyn also said she was tired of seeing “groups, foundations, and NGOs from other regions wanting to teach [how to think about and solve their problems], without knowing the context’.

This group of women was co-founded as a political act from the grassroots, from the reality of San Luis Potosí and as an act of protest. Interestingly, at the beginning the objective was just to chat about the political context, but it has now become an example of local feminism and of rebellion.

Thus, a school of sorts was born, unplanned at first, but non-partisan. “We know that the parties here, in Potosí, Bolivia and, perhaps, in Latin America, use women’s struggles as a tool”. It is very important “to be thinking women and to find solutions to our own problems”, says Evelyn.

Officially, Mujer de Plata was born as a WhatsApp group at the end of 2017, after many failures because in Potosí “they felt there was a kind of bubble,” without activism or many demands, except for those of COMCIPO, or the Potosí Civic Committee. “Potosí is not just about mining and royalties, there is also violence and terrible human development,” says Evelyn. The creation of a protest group was crucial.

Evelyn Callapino, co-founder of Mujer de Plata, walking with a megaphone in hand.

With a megaphone in hand, on the street, Evelyn Callapino radiates rebellion and energy, admitting that the first time she picked up the megaphone was in 2018 when she confronted the former governor of Potosí, Juan Carlos Cejas, rebuking him for saying that feminism is the opposite of machismo. That time, her brother Osman Callapino saw her and said, “You become someone else when you’re holding the megaphone.” In other words, you could see the strength she transmitted, which even inspired him to write a poem. “That woman who didn’t just use her teeth to smile, she could bite if necessary […]”

Today, although it has taken a long time to cultivate the use of the megaphone, it has become a school for new members. “In Potosí, it has been frowned upon for a woman to shout because we have always been very conservative”. From the beginning, the megaphone has been like a test to be part of Mujer de Plata.

At the same time, knowing how to graffiti and agreeing to do it is essential. The members of “Mujer de Plata” know that graffiti is crucial and they practice it constantly as a tool of protest with powerful slogans. They remember their first graffiti on the walls of Potosí, when they began to radicalize, of which the slogans that still survive are “The cooperativists plunder the hill like they rape women” and “We are silver that does come from the mine, but from rebellion.” The latter is now part of the collective’s official slogan.

Mujer de Plata’s megaphone and sign in the old town of Potosí, Bolivia.

Creation of the Mujer de Plata’s Logo

The first Mujer de Plata logo included the map of Potosí, the Rico Mountain, and the figure of a “fit” woman. However, it did not capture the essence of the collective. For this reason, María René Soria Rentería, co-founder of Mujer de Plata, decided to develop a logo based on local feminism in order to understand and reflect on the essence and value of the collective’s rebelliousness.

Logo of the “Mujer de Plata” collective, designed by María René Soria, co-founder of Mujer de Plata

“It took me about seven months to give birth to the logo,” she said. In the process of creating it, Mane reviewed logos of feminist organizations and realized that the common use of purple and green was Eurocentric, so from the perspective of Mujer de Plata, the collective did not want to replicate it and be that feminism.

The idea was to create something very distinctive to Potosí, “the most Potosí thing is the mountain.” It was unimaginable to conceive of a logo without the Rico Mountain. “From my house, I saw the mountain every day and it looks deformed,” said María René. With the idea of caricaturing the mountain and talking with the sisters from the collective, they concluded that “the mountain is a woman, not a man, she is a virgin who is raped every time they extract the ore. They ask the devil, the guy in charge of the mine, for permission to rape her. That is the analogy we have used.” It has helped us to understand. So, “the mountain is a Mount of Venus.”

She also saw how Potosí is understood by the population. “People talk about respecting our colonial land, our Imperial City,” that language and its expression also appear in local songs. “However, for me, being a colonial Potosí is not good, that is to say that we are Spanish, or that we feel that way, and it’s even a bit hypocritical.” Especially knowing that “our ancestors have been violated and exploited by the Spanish”.

Uprooting that idea was the most important thing. “What I did was to portray a woman, to structure the body, it is not a stylized body,” with the aim of breaking stereotypes and representing the violated and exploited bodies of the Potosí women. “Moreover, that body is my body, it is drawn based on my body,” says María René.

The logo contains symbolic elements, such as the Mount of Venus, seeds, the graffiti text “Plata que no sale de la mina, sino de la rebeldía” (Money that does not come from the mine, but from rebellion), which is located in the navel of the body, as symbolism of a feat, a paradigm of Potosi feminism, the power to give life to new actions in the struggle for social transformation. The hands are a symbol of care for the earth and Potosí and for work. Finally, it is a visual reminder from a local feminist perspective.

The designation of “personas non gratas” turned out to be a turning point, a watershed for this non-partisan collective that ended up strengthening them. “We are not interested in being liked by anyone” and they affirmed that the most redeeming thing is that they have reaffirmed their principles. For this reason, too, the logo was redesigned, like a rebirth and a re-founding, an identity was created that screams Potosi rebellion.

How to Be a Mujer de Plata?

To belong to Mujer de Plata, people not only have to go through a formative process but they also “have to do activism in the street, they have to stay organized and support each other, and that is one of our principles,” says Ángela Uzuna Bobarrín, co-founder of Mujer Plata. That is to say, taking action through physical and psycho-emotional accompaniment in cases of violence, demonstrations, getting prepared, carrying things, being there through thick and thin.

Vanesa, a member of Mujer de Plata, putting up a banner.

The requirements to be a Silver Woman are to have a good heart, to be a good person, not only in words but in actions, not to be indifferent to injustice, to be “non-partisan.” Double-dealing or remaining with another organization is not allowed, you can only be with one organization, and be at the grassroots level, in the streets, absolutely. “Something that differentiates us from other organizations and NGOs is that there is constant training, not of the elite but of knowing what is going on and staying informed,” said Ángela.

“Based on our knowledge, we analyze and have a position on something” because four years ago they had an experience where they were manipulated, where they were using discourse like a political party. That’s why they began to radicalize. ”We weren’t interested before, we’ve been changing. We are growing more, we are not static […] political parties are very instrumentalist, opportunistic, too basic, calculating, repetitive, and with a lot of improvisation,” Ángela continued.

“Our principles are self-convened, autonomous and non-partisan,” whereas the political issue taints the process. ‘We are political, we do politics, micropolitics from the experiences of our members, we are transcending beyond all of that,” Ángela emphasized. They decided not to belong to other organizations in order to build a solid base. “I have seen several young people who belong to various organizations that have budgets and are there for their own convenience.” For this reason, the collective screens the members to find out who comes out of convenience and who is working wholeheartedly.

The sisters recall that “sometimes, we are called upon to go out and march for any old reason, but we are not a strike force.” They do not take to the streets for the sake of it. “We review the cases, we filter them, we are not going to protest without reason or arguments, because we have to pace ourselves.” On several occasions they used to put their bodies on the line under any circumstance, “before we were more passionate, being sick or in my case, recently operated on, I would still mobilize. We have seen that it is not healthy because the femicide [court] cases also lasted all day, and we were not paid for any of it. Finally, it is about lessons learned and choosing which struggles to support, because we are not stupid.”

Women supporting each other

The case of Gabriela (fictitious name) is an example of flourishing among sisters in struggle. Gabriela is a victim of femicide (of her mother) and infanticide (of her younger sister). “Gaby came to us because the state had done nothing to help her,” said Angela. No one had intervened or cared for hre and her three orphaned siblings. Neither the Ombudsman’s Office nor any NGO. For that reason, Gabriela approached Mujer de Plata. The institutions “have only focused on trying to capture the father and see who the suspect is.”

Girl with megaphone in hand, next to the Mujer de Plata sign.

Gabriela, as the older sister, contacted Ángela and Evelyn two months after the death of their mother and the infanticide of their younger sister. “We asked her, how have you been sustaining yourself this whole time?” She said, “my mom bought enough food and we are living off that.” They asked her about her siblings, about their situation, Gaby replied that she was taking care of them.

“We intervened as a collective, we contacted the Ombudsman for the Rights of Children, so that they could give the older sister legal guardianship, so that she could ask for support through that document.” Evelyn contacted SOS Children’s Villages to ask them to help Gabriela and to enroll her siblings in a sponsorship program. “So, what is being done about femicides, where do the orphans end up? We provide support for the victims.” The situation is emotionally draining, and who holds up under it all? Mujer de Plata.

When they asked Gabriela if she wanted her siblings to go to an orphanage, she fearlessly replied no, I’m going to look after them. “Now, she is mothering […] she works, she studies,” she is going through the whole process and making room for activism. “It’s not about when I have time, it’s about structuring something, it’s an example of changing small worlds,” reflects Angela.

“Her siblings are very fond of us and have given us drawings as gifts. We are there for them and are also helping her get a scholarship, so she can continue studying. She is super hardworking and super active. So when she wants to break down, we go to support her and provide her with emotional support,” said Evelyn.

They recently helped Gabriela transport supplies from SOS Children’s Villages, since she lives very far away. “Those things that are so simple […] it’s nice to help and that’s what being committed is all about”. Gabriela’s case is special, since she takes care of three little brothers and sisters, but after finding Mujer de Plata, they are blossoming together. “Gaby is a walking school. I see her and I love her very much, she comes, she wants to learn, and she stands behind other women”.

On the other hand, in the case of the feminicide of Pamela Rocha, there was a terrible erosion of support due to the abandonment of the State. The collective provided its own resources, both economic and in terms of time and dedication, basically legal advice, without receiving anything in return. They even received death threats. The culprit of this crime was eventually extradited from Argentina and sentenced to 30 years.

In another case, they provided support in a process where they wanted to evict an elderly person from their home. What the collective did was not to sponsor the case, but to accompany the person to all the hearings, and, on occasions, help to explain the legal lingo in a simpler language, and in the end she won the case.

“We were just sitting there with her, really,” however the person was very grateful to the collective. It’s funny how she found out, ‘through an interview we did on Radio Kollasuyo where we talked about violence and that they are not alone,” and that is how “we’ve started to get to know each other […] She sells cakes, sometimes she runs into us and invites us for cakes as a way of saying thank you.”

Evidently, Mujer de Plata is a school for understanding collective work and is now “the only organization of feminist women in Potosí,” said Mane.

Members of Mujer de Plata with spraying cans in hand.

Through the Breaking the Mould report, collectives have realized their importance in challenging norms and behaviors. This strategy—essential for change, both individually and as a collective—allows people to reconstruct their concepts of gender, identity, and society from a more inclusive and egalitarian perspective.

Members of Mujer de Plata, with the mountain range in the background.

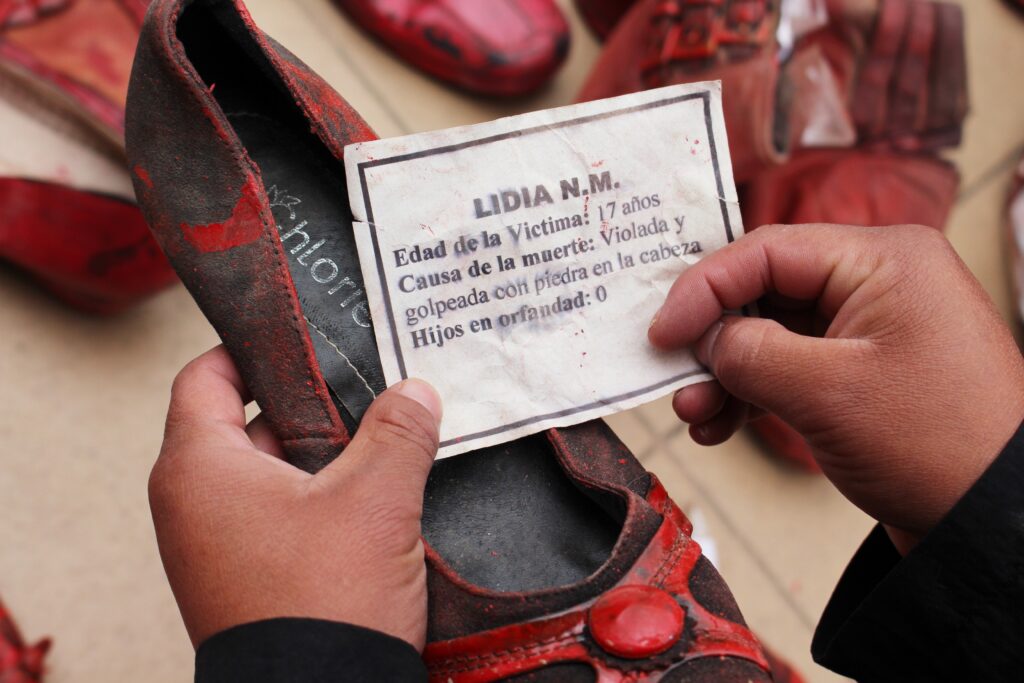

The megaphone, the graffiti, the red shoes, and the carpet of shame became weapons against machismo and symbolic expressions in the face of collective injustices. By understanding collective work from a holistic perspective, Mujer de Plata is clearly a walking school and is now an organization of feminist women from San Luis Potosí with a holistic perspective, as its co-founders point out.